The greenest desert in the world, the Sonoran Desert is also the most diverse. After rain, it’s easy to see why. Hundreds of different varieties of cacti, shrubs and trees are suddenly green and healthy-looking. Wildlife may come out from hiding, and you understand why this is the greenest desert.

However, rain is rare in any desert, and the Sonoran is no exception. We haven’t seen any in several months - last I remember seeing on the news it was over 92 days - and that was a few weeks ago.

And when I hike in the desert, I notice this lack of rain.

Giant saguaros reach up to the sky, their columns thin and shrunk.

Prickly pear cacti look like flattened pancakes, shriveled up.

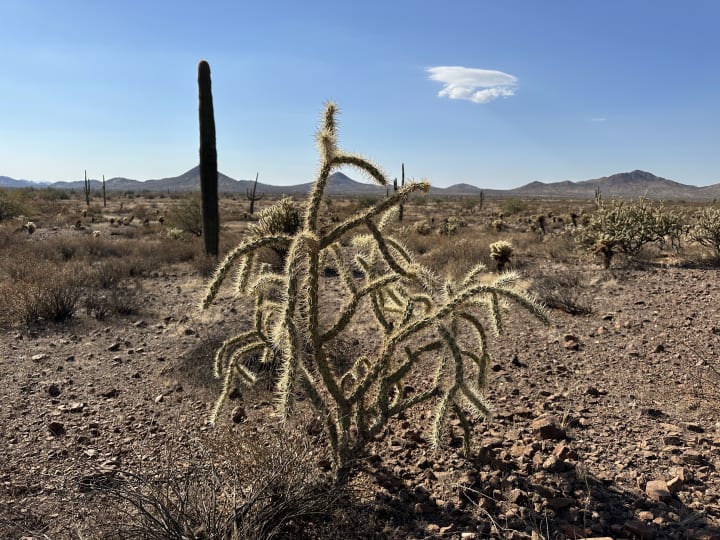

Cholla cacti look scarier than usual, their spines seem longer against their shriveled up stems.

The creosote bush, the shrub that gives the desert the distinct smell of rain when wet, looks almost dead, its oily leaves tiny and sharp.

All these plants, and thousands more, are waiting for rain. And while waiting, they conserve every ounce of water they absorbed and have been storing since the last rain they experienced. Which was months ago.

How do they do it?

The giant saguaro illustrates it in the most obvious way.

A columnar cactus, the largest in the US, it stores water in its trunk, which swells like an accordion after rain. As it ages, after reaching about 75 years, it may grow arms that also help store water. During long periods of drought, the cactus slowly uses up this water, while waiting for the next rain.

However, climate change (among other things) is threatening saguaros, since higher daytime and night-time temperatures reduce their efficiency of using their stored water, which may cause them to die before the next rain. Or, if the drought is too long and they deplete all their water storage, during a new storm they may absorb too much all at once, becoming too heavy and topple over.

So, we all hope that they don’t need to wait too long for the next rain.

Other columnar cactus species, as well as all types of chollas, use their stems the same way, storing water in their trunks and stems and using it until the next rain, when they swell up.

The prickly pear cactus uses its pads the same way; they swell up to store water and gradually flatten while waiting for the next rain.

On the other hand, the creosote bush adapted to long drought periods differently. Their tiny, pointed leaves are great water savers because they release less moisture than a big leaf. The waxy coating on their leaves helps prevent water loss. During and after rain, as they get wet, their leaves release fragrant chemicals, resulting in the “smell of rain” those of us living in the desert know so well. During drought between rain, the creosote bush loses its typical fragrance, while waiting for rain.

And then there is the unique palo verde, Arizona’s state tree.

The palo verde tree adapted to this constant waiting for rain in a unique way. Its bark is fully green (giving it its name that means “green stick” in Spanish, so it can photosynthesize and produce sugar even without its leaves. During drought, this allows the tree to drop its leaves to conserve water.

Besides being unique and important on its own, the palo verde is also the primary nurse tree for young saguaros.

Extremely slow growing, saguaros only reach about one to one and a half inches in the first eight years of their lives. While young, they need protection from a larger tree, a so-called “nurse tree.” Which, most often, is a palo verde (though it may be a mesquite or ironwood, too).

When walking through the Sonoran Desert, I always notice younger saguaros growing near, or under, a palo verde tree. The palo verde protects the young plant, offering it shade to allow it to mature. I remember this when I see larger, healthy saguaros growing near a palo verde. That tree was its nurse tree.

As the saguaro grows, its much older nurse plant often dies. It may be because saguaros compete for water and nutrients from the soil in the area. However, it is probably just natural aging, since palo verde trees rarely live past 100 years old, and they are usually much older than the saguaros growing in their protection. And the slow-growing saguaro is considered an adult plant at 125 years of age, when it may be around 50 feet tall and weigh about six tons after rain (their weight fluctuates with the rainfall).

Both saguaros and palo verde trees are keystone species of the Sonoran Desert, meaning they are vital in holding up the desert ecosystem, providing food, shelter, and protection for hundreds of species, from birds to insects and other plants.

All the species living in the Sonoran Desert are now still waiting for rain. A cloud or two may show up as a promise of rain, but it passes without much of a shadow.

So, the plants of the Sonoran Desert continue waiting. In fact, they are waiting for rain most of their lives. And then, when they finally get the long-awaited water, they enjoy it, then store it for the next time.

Hope they don’t need to wait too much longer… We often get some rain in December, though true rain usually comes in late January and February. For now, they need to wait a little bit longer…

To see the beauty of the Sonoran Desert after rain, and understand why it is the greenest desert, you can read about it on Wanderer Writes:

Rain in the Desert: Monsoon in Phoenix

Hiking in the Sonoran Desert Preserve

Thank you for reading Letters from a Wanderer!

Wishing you all a Happy Holiday Season, no matter what or where you celebrate!

Emese

Sad to hear about the lack of rain in the Sonoran, but guess it makes sense as SoCal and AZ in general ache for the rains. Great facts, though alarming.