Change of Plans: Sedona to Montezuma Castle

Fleeing Congested Sedona Achieved A Better Time In A Quieter National Park - Letters from a Wanderer # 48

On a beautiful spring day in late April, we woke up with the thought of revisiting Sedona, the town that inspired us to move to Arizona. It was a Thursday morning, so we expected to find it quiet.

While we often revisited the gorgeous red rocks in the first decade of being Arizona residents, we’ve been avoiding the town lately. The rocks are still the same, but the town is not. Too crowded, too built-up, while whole new shopping centers sprouting up almost every time we drive through, for us, it became one of the poster towns for the Eagles song quote, “call something paradise, kiss it goodbye”.

Don’t get me wrong, I still love the town. I just have a problem with crowded places, with being surrounded by too many people, especially if some of them are loud and obnoxious. Which are at least half the people visiting Sedona at any given moment.

Plus, all the new buildings popping up take much of the magic away from the surroundings.

But sometimes, I still miss it. And it’s relatively easy to enjoy the surrounding red rocks without the touristy areas. Or so we thought.

In the past, we always visited on weekends or holidays because of work and school schedules, so we thought we would find it bearable on a Thursday morning, in April.

We were wrong.

Congestion started as soon as we drove into town. We got off the main road and drove towards the Chapel of the Holy Cross. Not because we wanted to go to church. But it was the first site in town we stopped at 33 years ago, during our first trip to Arizona. We loved the panoramic view from there and wanted to revisit it.

The line of cars we were stuck in was moving at a snail's pace towards the church on top of the hill. At first, we thought it would open up as people pulled into the parking lots.

Wishful thinking.

After a few minutes of this, we turned around, parked lower along the street, and walked up the hill.

The views were still as gorgeous as ever!

However, more homes and buildings peppered the valley under them.

We found a not-so-quiet spot and enjoyed the views of the surrounding red rocks, trying to ignore the comings and goings of groups of people, large and small, acting like they were the only ones there.

Eventually, we left and got back to the car.

We still planned to drive further into town and revisit some of our favorite spots.

But as we sat in traffic, I realized I was getting too annoyed to enjoy the day.

“We don’t need to go into the town,” I said.

Jeff agreed and turned around.

“We can stop at Montezuma Well instead,” I suggested. “It is usually deserted, and we haven’t been there in a few years.”

So that’s what we did.

The road leading to the National Park was quiet, as usual.

Along the way, we even noticed a small Thai restaurant where we stopped for lunch.

Montezuma Well

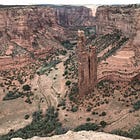

Part of the Montezuma Castle National Monument, Montezuma Well is a desert oasis surrounding a natural lake.

To understand this waterhole’s existence in the desert, we need to know just a bit of geology.

Arizona is home to the Verde Limestone Formation, a layer of travertine limestone deposited above shallow lakes that covered Verde Valley a few million years ago.

According to the sign near the well,

The water bubbling into Montezuma Well today fell as rain and snow atop the Mogollon Rim over 10,000 years ago.

This is hard to fathom, so I kept reading and re-reading to make sure I understood.

Between 10,000 and 13,000 years ago, precipitation atop the Mogollon Rim began percolating down through hundreds of yards of rock—basalt flows, Coconino Sandstone, Supai Group, Hermit Shale, and others —until it reached the relatively permeable Redwall Limestone. Once there, it trickled down toward Montezuma Well. Here, the water reaches an underground dike of volcanic basalt that forces it back to the surface after its ten-millenium journey.

On its long way up, the water eroded an underground cavern until its roof collapsed and created the sinkhole, similar to the cenotes of the Yucatan Peninsula, we see today.

To understand it better, they added an illustration. It made more sense to me that way.

The resulting well created an oasis in the Arizona desert. Well, sort of.

The water in the Well has extremely high levels of dissolved carbon dioxide, making life impossible for fish, amphibians, and water insects.

Without them, this water in the desert created a unique habitat. It is home to five creatures found nowhere else on the planet: a miniature shrimp-looking amphipod, a leech, a tiny snail, a water scorpion, and a diatom (one-celled plant).

The water still flows constantly. Every day, the Well is replenished with 1.5 million gallons (5.7 million liters) of new water.

However, the water level stays constant, doesn’t overflow.

Not on the surface, at least.

Instead, it overflows through a long, narrow cave in the southeast rim to reappear on the other side at the outlet.

The water from the well enters an underground stream through a long, narrow cave and flows through 150 feet of limestone before re-emerging on the other side of the rim.

This is where we find more trees, more vegetation, this is where it feels like an oasis.

The emerging water also leads to an irrigation ditch, sections of which date back about 1000 years.

Ancient people recognized the value of the constant supply of warm, 74-degree water and used it to make a living in the area.

One of the cultures to build homes here were probably the Hohokam, from the Salt River Valley in southern Arizona, also known as the “canal builders”. They channeled the water leaving the well into a canal that irrigated acres of corn, beans, and squash, crops called the “three sisters”.

The Hohokam likely lived alongside the Sinagua, a culture that lived in the Verde Valley even longer. They were the ones who built the small cliff dwellings in the cliffs around the Well,

and lower, near the water, where bats took up residence over the past centuries.

Over time, they built more than 30 rooms along the rim. Their pueblo was one of 40 to 60 villages that dotted the banks of waterways throughout the valley.

By 1425, they migrated to other places.

Since then, the rooms at Montezuma Well have stood empty.

However, the builders’ descendants, the Hopi, Zuni, and Yavapai, all have oral histories of their ancestors living here, and return to honor them.

Montezuma Castle

It was getting late in the day by the time we left, but we still had enough time to stop at Montezuma Castle before its closing time.

The main side of the National Park, Montezuma Castle, is where you’ll find the park’s headquarters. To drive there, you have to get back on the highway and out at the next exit, but the two sides are not far from each other.

Understanding that we are in Arizona, you might realize that Montezuma Castle (as well as Montezuma Well) is a misnomer.

Of course, the Aztec king Montezuma never set foot in this part of the world. What’s more, these cliff-dwellings date from centuries before he was born. Yes, I believe they should change the name (they started doing it with other monuments), but at this point, the future of National Parks is unfortunately too shaky to worry about names.

Regardless of its name, the largest cliff dwelling in the Valley is amazing! No wonder early settlers thought it was a castle. And, since the only name they knew from the ancient world on this continent was Montezuma, that’s what they called it.

People who built the cliff dwelling had nothing to do with the Aztecs, although they traded with them.

As far as they were from each other, ancient people in the Southwest traded regularly with the Maya and Aztecs from way down south. If you walk through the museum at the site, you’ll see evidence of it.

But since we had little time before closing time, we didn’t spend time in the museum (we’ve been there many times before), but walked out to the cliff dwelling.

The park still had visitors, but it was far from being crowded like Sedona. We walked the short trail in the shade of Arizona Sycamore trees.

Native to the state, this unusual tree is easy to recognize for its constantly shedding bark, showcasing white, brown, and green colors, and growing up to 80 feet tall.

We know they also grew here during the time Montezuma Castle was inhabited, since the builders used its thick branches to build the main beams of the cliff dwelling.

At the far end of the loop trail, we reached the “castle”.

The five-story-high cliff dwelling is one of the best-preserved in the country. Its rooms sit on ledges of natural caves on a 150-foot-high limestone cliff. Featuring about 20 rooms, it housed an entire village, between 600 and 1100 people.

Since no one knows what they called themselves, we call the people who built Montezuma Castle (and the cliff dwellings on the cliffs of Montezuma Well) Sinagua, the Spanish expression meaning “without water.”

Dr. Harold Colton, founder of the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, came up with the name in 1916, when he first identified the culture. He based it on the Spanish name for the San Francisco Peaks, “la sierra sin agua,” the mountain without water.

Two separate groups of the Sinagua lived in the area: the Northern Sinagua, near the San Francisco Peaks (their ancient structures protected in Wupatki and Walnut Canyon), and the Southern Sinagua, in the Verde Valley, where they built the structures at Montezuma Castle and Well, and Tuzigoot.

Though we don’t know what the Sinagua called themselves, in the past few decades we learned what their descendants, the Hopi, call them: Hisatsimom, people of the past.

The structures they left behind are protected by the National Parks and Monuments surrounding them.

Montezuma Castle became a National Monument on December 8, 1906, the third park or monument (following Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado and El Morro National Monument in New Mexico) dedicated to preserving Native American culture.

At first, visitors were allowed to climb up the cliff dwelling and even enter it. However, the direct contact started damaging the structure. So, in 1951, they restricted access, and now we can only walk close to it and admire it from the trail.

Since visitors don’t enter the cliff dwelling, it makes a perfect home for bats. Some of the largest bat colonies in Arizona, of 14 different species, live here. That’s half of the 28 species living in Arizona.

Two of those species, the Western Red Bat and Townsend’s Big-eared Bat, are listed as endangered species, in need of conservation, so the park offers them a protected area to thrive.

We didn’t see the bats, since it was still daytime when the park was closing. But knowing they are there is enough.

The US National Parks and Monuments protect so much more than meets the eye. Even in a relatively small park like Montezuma Castle (including both the “castle” and the Well), they protect unique environments, including ancient structures, endangered species, and living creatures not found anywhere else on the planet.

We left when the park was closing and made our way back home.

In the end, it was a great day trip, even if it started with us getting annoyed by crowds in one of the most beautiful places on the planet.

Thank you for reading another issue of Letters from a Wanderer!

If you enjoyed it, please give it a “like” and share it so others can find it, too.

And, if you came across it on Substack, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Or, consider buying me a coffee as a sign of appreciation for this post alone.

Thank you!

And please support our National Parks in any way you can!

All the best, and happy travels (especially through National Parks),

Emese

Other posts I wrote that you might enjoy from National Parks:

I loved visiting Montezuma’s Castle. Sedona is great, but getting out of town is even better.

Thanks for taking us on this visit and introducing me to the unique habitat around Montezuma’s Castle and Well. Although I lived in Arizona for several years, I never went to Sedona or the national park there.