We Reached Cobá - Climbing the Tallest Pyramid on the Peninsula for the First Time

Travel Tales from the Land of the Maya #6

Welcome back to another installment of Travel Tales from the Land of the Maya, stories.

For those of you awaiting this installment, thank you for your patience. I hope you enjoyed the posts featuring my latest trip to Copán.

If you are new here, you landed in the story of my first trip to the Yucatan Peninsula in 1995. You can read the first 5 posts of this story:

The narrow road flanked by thick jungle was empty, except for an occasional beat-up car. Once in a while, we drove by Maya men on rusted bicycles, carrying machetes as they rode onto the road from barely visible trails leading into the jungle.

Heading inland just past midday, it was getting hot, an oppressive, humid heat I’d never experienced before. We drove on in quiet anticipation of our next destination, the archaeological site surrounded by jungle, Cobá.

The small Maya1 town surrounding the archaeological site seemed deserted when we arrived.

There were few cars on sight (and even the ones we saw were stopped), few people walked on the street, only the town's stray dogs lay lazily along the road, and sometimes on the road. Looking as tired as we felt, they didn’t even bother moving from the road. We drove around them instead. Past the main road, we turned onto the dirt road leading to our destination hotel, the Villas Arqueologicas, as deserted as the town; We seemed to be the only guests. Siesta time in Yucatan, we thought. During the oppressive midday heat, everyone was resting inside.

Later, when the sun arched and it was more pleasant, we walked out towards the ruins and stopped at the lake.

As we walked on the dirt road along the lake, we noticed the pyramid closest to the entrance, called La Iglesia, above the tree line.

Reaching above the jungle canopy, it stands 74 feet (22.5 meters) tall, and it’s the second-largest pyramid at the site. Built in nine tiers over hundreds of years, it dates from the Late Classic Period of the Maya civilization (around 550-900AD), though the temple on top (eroded, you can’t see it) was added later, in the Post-classic era.

The next morning, after entering the archaeological site2 , we saw it up close.

We couldn’t resist the urge to climb it. I got as far as the stairs lasted; It looked too scary for me to climb farther. However, Jeff continued, along broken stairs. I knew better than to try talking him out of it. Instead, I said, “Be safe,” and hoped he knew what he was doing. He was as agile as a mountain goat, climbing through the rubble. From the top, he yelled down, “I can see Lake Macanxoc from here!”

Cobá means “waters stirred by the wind,” a fitting name considering the site’s location, near two large lagoons, Lake Cobá, and Lake Macanxoc.

We saw Lake Cobá and walked along its shores the previous night, however, Lake Macanxoc was not an easy lake to see, lying in the jungle somewhere in the archaeological site. So, I knew it was a big deal to spot it. It made me try climbing after my husband. After a few steps scrambling through rubble, I thought better of it and waited for him to join me.

We descended the pyramid together and entered its rooms on the bottom floor.

They are closed now, but back in 1995, the site had few visitors, and nothing was off limits. If you walked in, you were on your own, no one bothered you; You could climb any structure you wanted, and enter any room you wanted.

The rooms under the pyramid (or rather on its ground floor), with no windows or any other openings, were pitch dark, so they made a perfect home for bats. I remember putting red tape as a filter on our flashlight to look for them. (We learned this trick during our star parties as members of an astronomy club.) The red light wasn’t bright enough to wake up the bats (just like it isn’t bright enough to interfere with night sky-viewing), but bright enough to help us see them. I thought they were so cute, sleeping together in clusters, hanging from the crevices of the Maya arches in the dark rooms.

In later years, we often took our kids there. Once, when my daughter was a toddler, she couldn’t stay quiet (as much as she tried), and she woke up some of the bats. Which made them screech and fly above our heads. As interesting as the experience was for us (it was the first time we heard bats screech), I know it wasn’t fun for the bats, so I am glad they eventually closed the rooms. With the huge number of visitors the site gets, it’s safer for the bats this way. Not to mention, safer for visitors if they don’t try climbing this pyramid.

From the Cobá group, we walked through the Ball court.

Then we turned onto the main trail through the jungle towards the rest of the site.

The jungle path was just as fun to walk on as exploring the ancient structures. Birds were singing in large tropical trees I hadn’t seen before, and army ants crossed our path, carrying leaves larger than themselves. We stopped often and stepped into the thick jungle at times, just to be enveloped by the trees.

Eventually, we got to the next group, Grupo Las Pinturas. The main structure in this group is the Pyramid of the Painted Lintel. A small pyramid, its value lies in the gorgeous paintings on the lintel of its temple on top. We climbed it - it was nothing compared to the Iglesia - and marveled at the painted lintel above the doorway.

Since it was close to midday by the time we were ready to move on, and the top of the pyramid was shaded by the palapa protecting the paint, we felt it was a great place to stop for a snack/lunch.

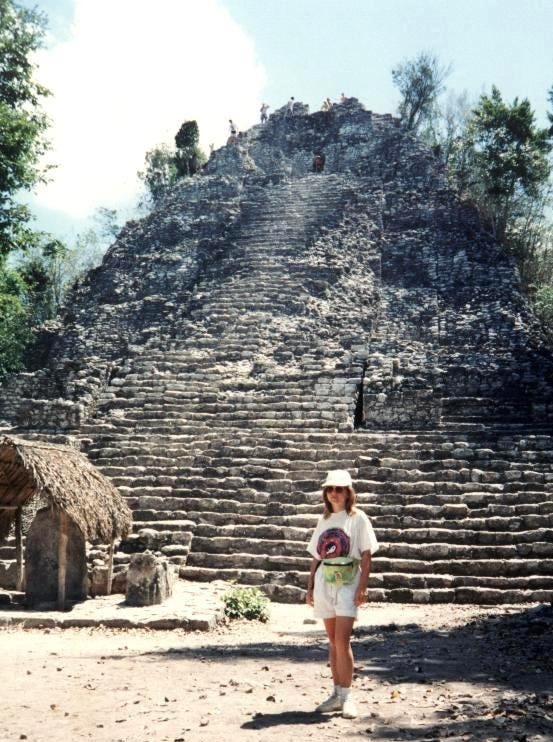

Eventually, we made our way to the tallest pyramid not only at the site but on the peninsula, the Ixmoja pyramid in the Nohuch Mul group.

As famous as this pyramid is now, at the time, few people knew of its existence. So, there was no need for a rope to help climb it, it was a free-for-all, climb if you dared.

Which, of course, we did. Though higher than the Iglesia, it was much easier to climb - all the way to the top. The stairs weren’t as eroded, and the top wasn’t in rubble.

Once on top, we entered the temple. Above the doorway, we recognized the Bee god, also known as the descending god, the same one we saw on the temples in Tulum.

We spent some time on top of the tallest pyramid on the Peninsula, enjoying the views and the breeze.

Eventually, we were ready to leave. Descending was much scarier than climbing it.

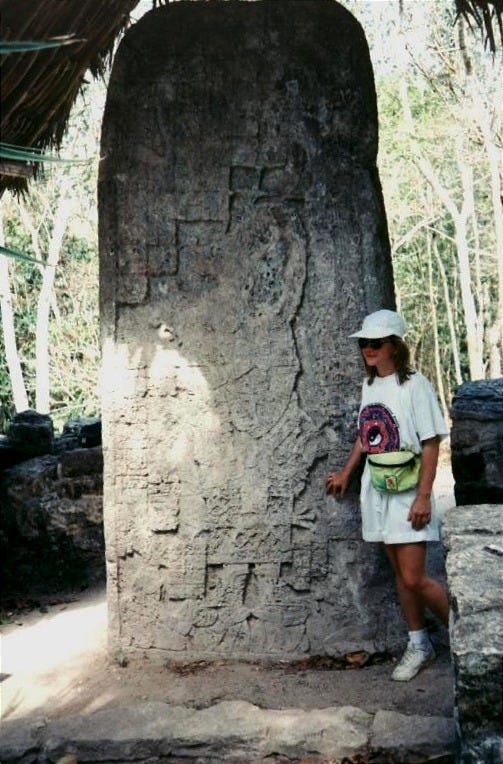

We made it back down and moved on to the Macanxoc group, filled with stelae.3

As a linguist, I found the writing system of the ancient Maya one of the most intriguing things about their civilization. So I was excited to see the stelae in Cobá, filled with writing surrounding a central figure. Though eroded, I could still recognize glyphs4. The easiest to find and understand were the numbers, but I recognized several others, as well.

Coba is home to Stela 1, featuring the longest Maya hieroglyphic text known so far, with 313 glyphs on it, carved on the front, back, and sides, recording dates from A.D. 653 to 672.

Seeing this exquisite artwork, and writing carved in stone, was the culmination of my visit.

We left the site at closing time, but knew we would return.

Hope you enjoyed reading this post about my old-time travels.

Until next time, wishing you all the best,

Emese

Though it might seem that the correct form should be Mayan as an adjective (and I’ve used it that way for years, following the general English grammar rules), this is not the case.

According to the Na’atik Language and Culture Institute, the only time the term Mayan is correct is when it refers to the family of Mayan languages (over 20 still spoken). (With one exception, the Yucatec Maya. Locals who speak it refer to it simply as Maya, so it is the accepted term for it.)

In every other instance, the term Maya is the correct form. Even when used as an adjective, including Maya civilization, Maya archaeology, Maya ruins, Maya town, and Maya people.

The archaeological site of Cobá was one of the most important city-states on the Yucatan Peninsula. Though first settled in the Pre-Classic period (300 BC – 200 AD) of the Maya civilization, the earliest structures we see at the site date from the Early Classic era (200 – 600 AD). And it wasn’t until the Late Classic period (600 – 900 AD) that Cobá became a serious power.

During this time, it was the regional capital of the area, and built most of its structures we admire today. Home to about 50,000 people, it held a strong cultural and political influence over the surrounding region. It also had ties or with the coastal port cities of Xel-Ha and Tulum. It also seems to have maintained powerful alliances with city states further south, like Calakmul, Dzibanche, and Tikal.

When Chichen Itza emerged as a rival power, the authority of Cobá started to decline. However, even after losing its political power around 1000 AD, Cobá remained an inhabited city until the 14th century, with a small population by the Spanish conquest. During its latest phases, people from nearby sites used it as a pilgrimage destination.

free-standing, stone slabs, filled with images and writing, usually telling the story of rulers of the ancient Maya, including significant dates in their lives.

Maya glyphs represent numbers, syllables, but also full words and concepts. It was this complexity of the ancient Maya writing system that made it so difficult to decipher.

We were there in 2022 and saw monkeys in the trees! It would’ve been so cool to have been able to climb it.

My wife and I visited Coba in the early 1990’s and I climbed to the top also. We spend years traveling to as many sites as possible. Thank you for reminding me of our younger days.